In Vanuatu, a South Pacific island nation that's a three-hour or so flight east-northeast of Sydney, Australia, the mystic figure known as John Frum is alive. Well, as much as he's ever been alive. He is not alone. John Frums, some will argue, "live" all over the world. Even in places you wouldn't expect.

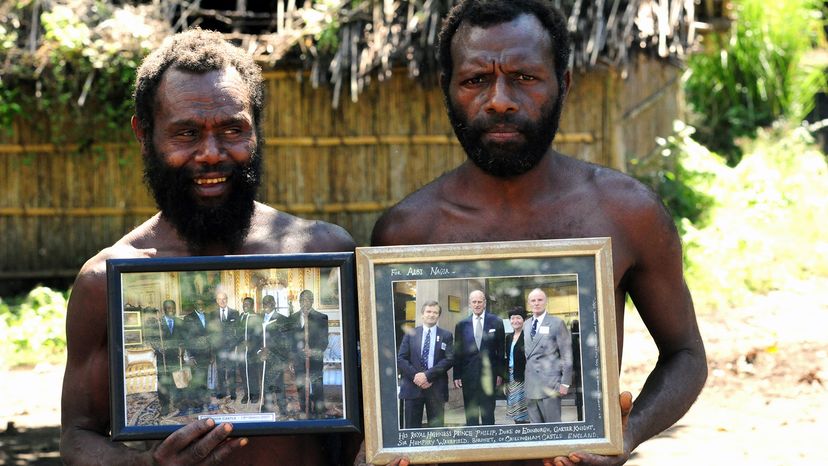

On the tiny island of Tanna in the Vanuatu archipelago — overall population about 250,000 — a vocal lot of locals still worship John Frum, a mythical personage often depicted as a white American World War II soldier (though he has been described in different ways). Every year on Feb. 15, Frum followers celebrate John Frum Day.

Advertisement

They raise the U.S. flag. They march in formation with rifles made of bamboo. Older islanders dress in military outfits, complete with medals. Years ago, they carved airstrips out of the jungle, complete with fake planes.

They honor John Frum and prepare for his return and the good times — and material things —that will come with it.

All this, it should be noted, for someone that outsiders believe sprung from the minds of elders high on kava, a local plant with slightly psychoactive properties.

Frum followers are leading examples of what many anthropologists label a "cargo cult," which is in itself a kind of moving target of a term that scientists now struggle to accept. The term has been used largely for groups in the Pacific, those in less-developed societies conducting what are seemingly strange and primitive rituals. The label is still used, but not as much. Calling something a "cult," after all, is a tad pejorative. Even the word "cargo" may not represent what it once did.

However the groups are tagged, they persist, some to the point that they have become legitimized parts of society. And they're not all relegated to the jungles of faraway islands.

"It's not just something that's in Vanuatu or New Caledonia or New Guinea. It's not just the 'primitive' spots," says John Edward Terrell, the Regenstein Curator of Pacific Anthropology at the Field Museum in Chicago. "That's why I argue that Trumpism is a 'cargo cult.' It's right here at home."

Advertisement