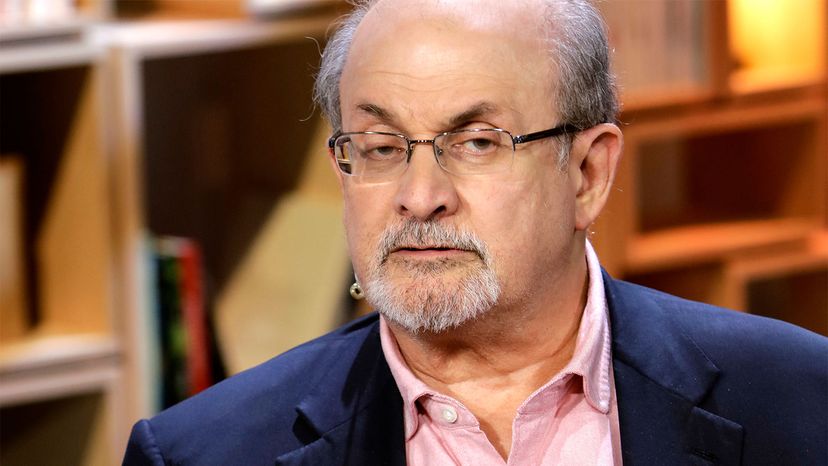

When news broke Aug. 12, 2022, that the writer Salman Rushdie had been attacked, many people immediately recalled the fatwa, or edict, calling on all Muslims to take his life, issued in 1989 by the Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Iran's Supreme Leader at the time. Khomeini accused Rushdie's 1988 novel, "The Satanic Verses," of insulting Islam and blaspheming against the Prophet Muhammad.

Violent riots and credible death threats sent Rushdie into hiding, and he spent the next nine years under British police protection. He did not emerge again until 1998, after Iran promised it would not enforce the fatwa, though it did not rescind it.

Advertisement

According to several intelligence sources quoted by Vice news, Rushdie's 24-year-old alleged attacker, Hadi Matar, had been in contact through social media with members of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, the military branch tasked with protecting the country's Islamic political system. However, there is no clear evidence that Iran was involved. Whether Matar was inspired by the decades-old fatwa remains a matter of speculation.

Given wide media coverage of the fatwa against Rushdie, some may conclude that a fatwa always means a death sentence.

However, a fatwa rarely calls for death, can be issued by a variety of religious authorities and is mostly of interest to a particular Muslim individual or community. My explanation of fatwas is based on expertise developed over several years of researching the writings of a Pakistani Muslim theologian and on my collaborative academic work with scholars of Islamic jurisprudence.

Advertisement