When President Harry Truman signed the Defense Production Act (DPA) in 1950, the threat was clear. The Korean War was just beginning. And the United States needed to gear up to help the Republic of Korea (we know it now as South Korea) ward off the Soviet-backed North to stop the creep of communism worldwide.

Congress came up with a plan to mobilize the private sector, Truman inked his "Harry S.," and the Defense Production Act became law, awarding sweeping powers to the federal government to compel private industry to produce materials and goods to help in the war. The Act has been authorized and reauthorized, amended and fiddled with, more than 50 times since.

Advertisement

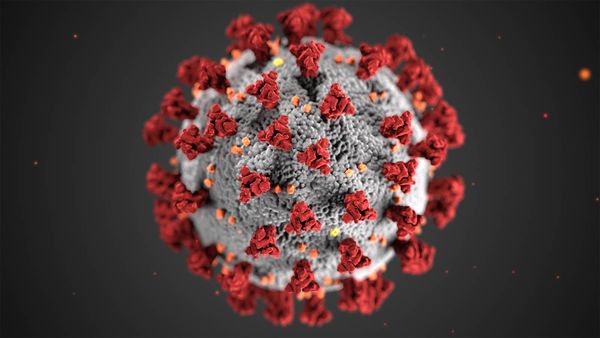

The threat to the United States is clear, today, too, if a little less conventional. The national emergency in the spring of 2020 is the deadly coronavirus. The concern is that the United States won't have enough personal protective equipment (PPE) like face shields, gloves, gowns and masks for health care workers, or ventilators and other medical equipment for those who are sick.

"It absolutely could be an effective tool. I don't think it's necessarily the only tool," says Peter Shulman, a history professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. "But it's the law that's on the books. It already exists. The authority already exists to do a good chunk of what we need. That's why it's there."

Advertisement