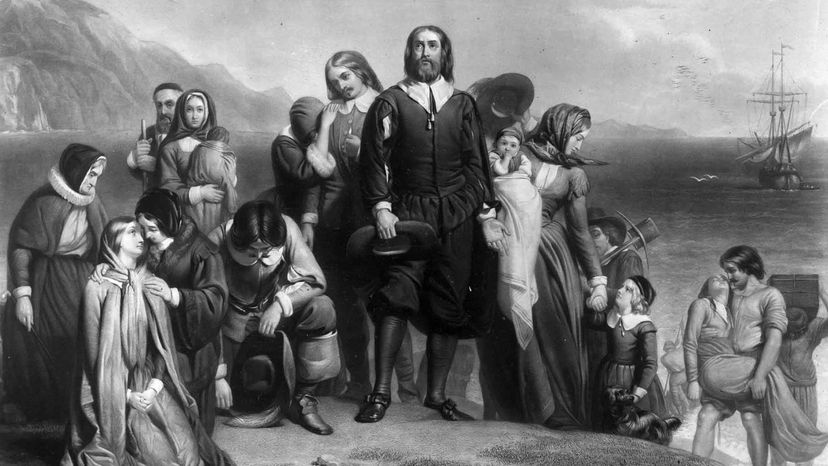

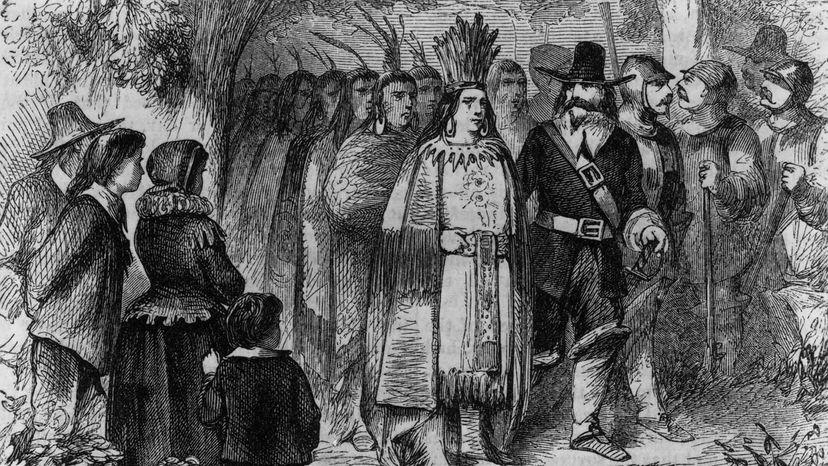

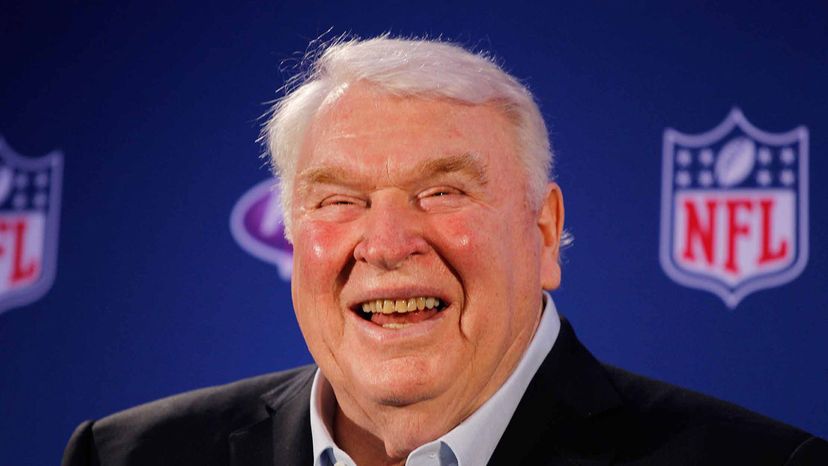

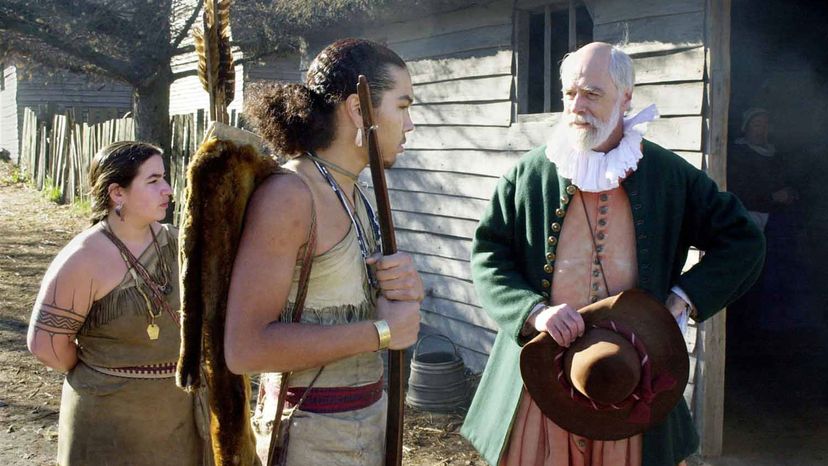

Thanksgiving: the quintessential American holiday in which Americans celebrate the fact that despite superstorms, unemployment and the 24/7 news cycle, life is pretty darn good for many in these United States. And oh yeah, something about tipping a tall black hat to the Pilgrims and American Indians who got this day of eating, drinking and football watching started some 400-plus years ago.

Just as many Christmas celebrators tear through eggnog and wrapping paper with the vague notion that the event is somehow related to a Jewish carpenter's birthday, so, too, do turkey day revelers heap on the cranberry sauce and gravy, sensing that this all has something to do with the native people and settlers who inhabited the land centuries before, but are not exactly sure what.

Advertisement

Perhaps the disconnect should be no surprise, given that modern Thanksgiving observances barely resemble the festivities of the "first" version of the holiday. Read on as we debunk some of the most notable mistruths concerning the original American day of thanks.