Key Takeaways

- The Titles of Nobility Amendment in 1810 proposed to revoke citizenship from Americans who accepted titles of nobility from foreign countries due to fears of aristocratic influence.

- In the 1828 Amendment to Outlaw Dueling there was a consideration to ban dueling, a common practice in the 18th and 19th centuries, but it failed to gain support.

- In 1860, a proposal to abolish the presidency and elect two individuals to share executive power was driven by concerns over slavery and presidential power.

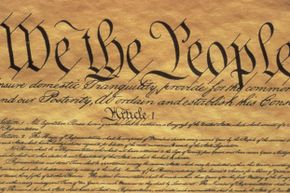

Every time you turn on cable news, there's a good chance someone is yelling about the need for an amendment to the United States Constitution. You're probably familiar with some of the more recent attempts, including proposals to require a balanced federal budget, define marriage as a union between a man and a woman, guarantee equal rights for women, ban flag desecration and reform the Electoral College. What you might not know is there have actually been more than 11,000 proposed constitutional amendments introduced in or recommended to Congress since the country's founding document was enacted in 1789 [source: Bernstein and Agel]. Like those listed above, many of them were politically controversial. Others, however, were just plain weird.

If it's been a while since your last civics class, here's a quick refresher on the constitutional amendment process. A two-thirds majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, or a constitutional convention called by two-thirds of the state legislatures, is required to formally propose an amendment. Then the amendment must be ratified by three-fourths (38) of the 50 states [source: National Archives]. The founding fathers designed the process to be difficult but not impossible, which is why, of the thousands of proposed amendments, only 27 became enshrined in the Constitution. Considering our list of some of the weird things politicians and activists proposed over the years, that's probably a good thing.

Advertisement