After President Donald J. Trump tweeted — without any apparent evidence — a claim that his predecessor Barack Obama had Trump's "wires tapped" in New York City's Trump Tower, it seemed only a matter of time until somebody would refer to Trump's accusations as Towergate. And the hubbub around the Trump administration's Russian relationships have taken the name Russiagate.

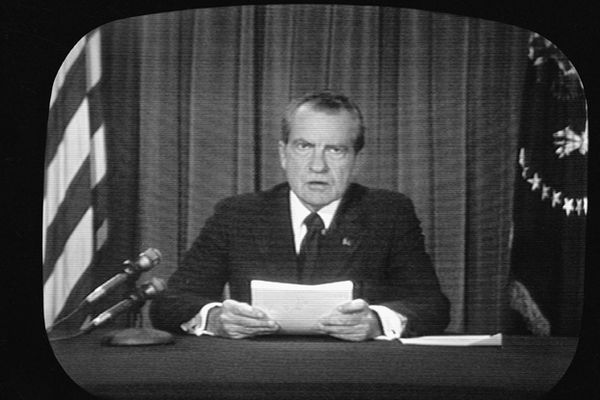

So where's all this "-gate" stuff coming from, anyway? Back in 1972, when operatives of President Richard Nixon's re-election campaign were caught breaking into the offices of the Democratic National Committee in Washington's Watergate complex. The expose of that scandal and the subsequent cover-up effort led to Nixon's resignation in 1974. But it had another consequence as well. Affixing the "-gate" suffix to the name of a scandal — whether great or small, actual or imagined — quickly became a convention for headline writers everywhere, and surprisingly quickly.

Advertisement

During the Jimmy Carter administration, the 1980 scandal over whether the president's brother Billy Carter and his links to the Libyan regime became known as Billygate. President Ronald Reagan was faced with Debategate in 1983 after it became known campaign staff had access to his opponent's briefing books before a debate, and in 1986, Iran-Contragate erupted when it became evident that officials in his administration secretly sold arms to the Iranian regime in exchange for the release of hostages, and then diverted the proceeds to illegally arm Nicaraguan contra militants. In the late 1990s, President Bill Clinton's legal troubles over his affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky became known as Monicagate. In the mid-2000s, the controversy that plagued the Bush administration over the blown cover of CIA operative Valerie Plame Wilson became known as Plamegate. After the attack on a U.S. consulate in Libya killed four Americans in 2012, some critics of the Obama administration started talking about Benghazigate.

And that's just in the United States. As Alex Seitz-Wal noted in The Atlantic in 2014, headline writers in at least 10 countries have grafted "-gate" onto their own countries' scandals — some of them considerably less consequential than Watergate. In the 2010s, Canada had its Pastagate over a Quebec French language regulation that compelled Italian restaurants to rename items on their menus. In 2016, a news photo of British Prime Minister Theresa May clad in costly designer leather pants was quickly dubbed Trousergate.

In recent years, the "-gate" suffix has migrated into other realms beyond politics — such as the NFL's Deflategate and Donutgate, the minor uproar that ensued after a security camera captured singer Ariana Grande licking a tray of donuts. And in 2012, on the 40th anniversary of the Watergate Hotel burglary, the proliferation of "gates" drove Washington Post writer Monica Hesse to lament that "all of the salacious occurrences of the world — the frauds and felonies and loose-zippered failures — have been corralled together to reside in one vast gated community."

With the suffix losing its scandalous ambiance, maybe it's time to take a break from naming any more "-gates." Perhaps we could call it Hiatusgate.

Advertisement