Nostalgia can be powerful. It inspires daydreams, it can propel a politician into power and it may serve as the foundation for an entire artistic movement. That's the case with dieselpunk, which is both a subgenre of speculative fiction and an artistic style that roots itself in the aesthetics and technological sophistication of the past.

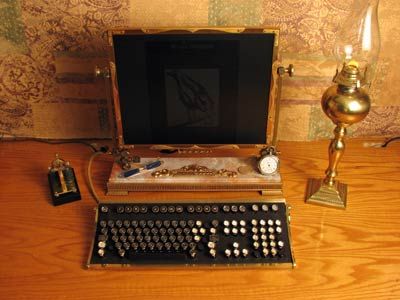

Dieselpunk is similar to another movement called steampunk. But while steampunk draws its aesthetics from the Victorian era of the late 19th century, dieselpunk traces its roots to the early 20th century. In general, dieselpunk draws inspiration from the 1920s to the 1950s. Everything from that era's architecture, art style, music preferences and pop culture shapes dieselpunk. Influences come primarily from the United States and Europe, though you might find some Japanese culture as well. Artists like Georges Barbier and pulp fiction writers like Raymond Chandler are the jumping-off point, much like H.G. Wells and Jules Verne serve as steampunk's foundation.

Advertisement

Like steampunk, dieselpunk marries these trends of the past with the capabilities of today's technology. One work of fiction set in a dieselpunk universe is the film "The Rocketeer." Set during the late 1930s, the story follows stunt pilot Cliff Secord, who becomes a hero after donning a special jet pack. The film -- and the comic book it's based on -- take the popular Art Deco style as inspiration for character, vehicle and set design.

Connecting today's technology with yesterday's aesthetic requires a do-it-yourself attitude. Many of the people interested in the dieselpunk movement are artists of one kind or another. Some work in canvas, others may bend steel and iron. There are dieselpunk storytellers who create works of fiction on the page, stage and screen. And there are video games set in worlds that fit snugly into the dieselpunk genre.

Advertisement