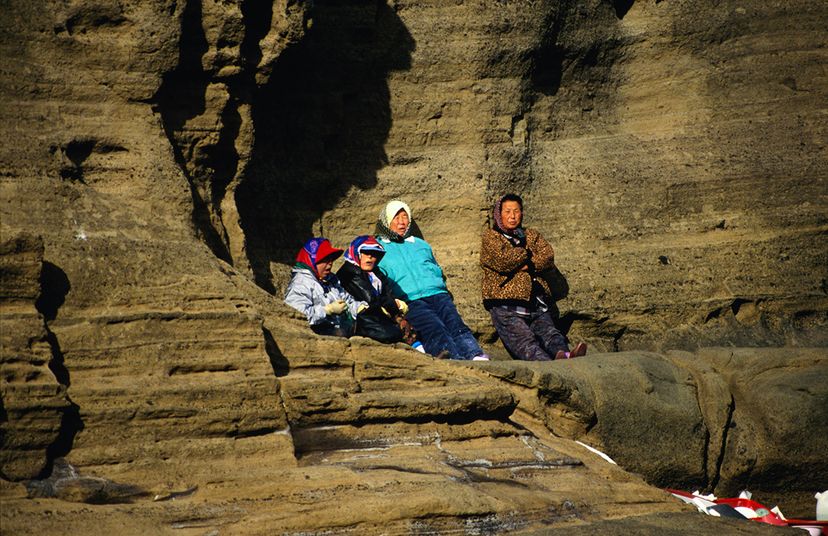

A group of women walk along a seashore. The water's cold, but they pull on their goggles, shrug into lead-weighted wet suits and wade in wearing flippers. They disappear beneath the water and embark on a free dive to the ocean floor, capturing sea urchins by hand. It's winter on the tiny Korean island of Jeju, which means the sea urchins are plentiful. For hours, the women agilely and efficiently harvest sea creatures while the air above the waterline hovers around 30 degrees Fahrenheit (negative 1 degree Celsius). These are the haenyeo — the "sea women" of South Korea. And they are a dying breed.

The haenyeo (sometimes transliterated as haenyo) dive for abalone, clam, seaweed, sea cucumber, sea urchin and squid without the aid of air tanks. To do so, they descend up to 65 feet (19 meters) below the water's surface and hold their breath for two minutes, sometimes more. Many have been diving since they were 7 years old, progressing to aegi haenyeo (baby sea women) at 15, and then perfecting their avocation well into their 80s.

Advertisement

People have gathered shelled creatures from the sea for ages, and the diving tradition on Jeju can be traced to the 5th century C.E. But female divers were noted in modern records for the first time in the 17th century. By the 18th century, diving was a profession primarily made up of women — at least on Jeju — either because there were particularly adept at withstanding the cool water, because it was an effective way to avoid the taxes applied to male divers, or both, according to historians.

Free diving on Jeju went on to become the exclusive terrain of the haenyeo, who call what they do "muljil" — water work — and assign divers three different ranks according to relative skill. The practice is similar to the sponge divers in Greece, shell divers in Australia, and pearl divers in the South Pacific and Japan. However, the Korean haenyeo today are one of the few groups that continue to eschew oxygen tanks in favor of holding their breath.

And the women who do continue to dive in the traditional manner are fewer still; the number of haenyeo peaked in the 1960s at about 23,000. In 2014, 84 percent of existing haenyeo divers were older than 60, and there are concerns that younger women will not keep the once-lucrative profession going. But even as the tradition appears to be fading, global interest is reaching new heights.

Groups of tourists are regularly bussed to see the women dive, an aftereffect of opening a Haenyeo Museum on Jeju in 2006; nine years later, the Jeju government spent $6.5 million aimed at preserving the tradition, paying for wet suits and insurance, among other things. And in 2016, UNESCO designated haenyeo a Cultural Heritage of Humanity. As the haenyeo are valued as a national treasure, supporters hope the focus also will shift to conservation of oceanic resources.

For more on haenyeo, and to see the iconic divers in action, watch this UNESCO video:

Advertisement