The concept of citizen's arrest became enshrined in English common law, and eventually was accepted throughout the U.S. as well. The practice has survived out of tradition, as "a reminder of earlier times when law enforcement was a private rather than a public duty," says retired UCLA law school professor Paul Bergman, who has written on the subject for Nolo.com, via email.

But, as Robbins points out, the statutes and case law regarding citizen's arrest vary from state to state. In Arkansas, for example, a citizen can arrest someone if he or she suspects them of having committed a felony without being legally liable for making a mistake, as long as the citizen had reasonable grounds for believing that the person was a criminal. In New York, in contrast, citizens get no such leeway. If it turns out that the person detained didn't commit a felony, the citizen is liable for false arrest, even if his or her intervention seemed justifiable at the time.

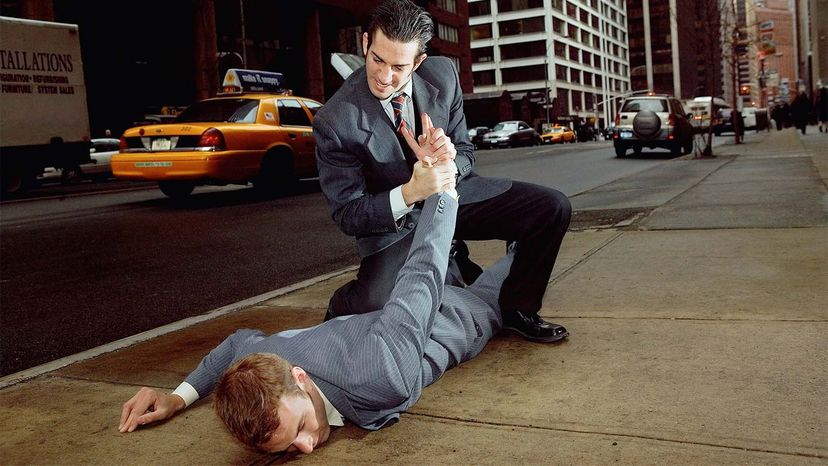

The potential for ending up in such trouble leads a lot of legal experts to caution people against trying to make citizen's arrests. "I think the main risk from a legal perspective stems from the possibility that your arrest might not be legitimate," explains Jay Anthony, a South Carolina attorney who wrote this blog post on citizen's arrest, in an email. "The types of offenses which warrant a citizen's arrest and those which do not are sometimes hard to distinguish. And since you're stopping someone by force, there's the potential for injury and so forth. While I think most officers and jurors would have more sympathy for a person stopping someone and making an arrest than for the criminal, there's potential liability and physical harm nonetheless."

Additionally, smartphone cameras make it possible for video of a citizen's arrest to go viral on the Internet, before law enforcement authorities have a chance to investigate and determine whether it was legally justifiable.

"Citizen's arrest is always dangerous," Bergman says. "Publicizing private arrests via social media may produce much higher private civil liability for mistakes."

While citizen's arrest often was and still is a spontaneous phenomenon, at times it's also been an act performed by organized groups. This 2006 Congressional Research Service report details the activities of citizen groups who patrolled the U.S.-Mexico border in an effort to stop illegal immigration, and noted that "the extent to which a civilian may use a state's citizen's arrest authority to apprehend, detain, and arrest an illegal alien is not clear."

Bergman sees a danger in such activism. "The citizen's arrest tradition is a policy that recognizes that since police officers cannot be everywhere it makes sense to allow one-off arrests by particular victims. Citizen's arrests should not replace policing policies and duties with armed forces."

Is a citizen's arrest something people should avoid doing at all costs, or are there any situations where it might be advisable, compared to the alternative of allowing a suspected lawbreaker to escape?

"This answer probably depends on whether you're asking me from a legal or practical perspective," Anthony says. "From a legal perspective, from a pure cost-benefit perspective, there are probably few instances where a citizen's arrest makes sense. That's particularly true given that our emergency responders are much more responsive than they were in the old days. If you have to wait a few days for a marshal to come to town, then a citizen's arrest is probably more appealing."

"Now, from a practical perspective – I'm a good Southern boy and if I can stop someone from committing a crime, whether it's a crime against me or someone else, I'm probably going to step in," Anthony adds. "That's particularly true if the 'bad guy' might get away altogether."