Black Lives Matter means a lot of different things to a lot of different people. It's a racial justice movement, a rallying cry, a social media hashtag and maybe even a political organization. For some, the movement is also a divisive force that has drawn a line between the police and the people and helped spawn some of the violence seen in the aftermath of high-profile, police-involved shootings. Even those detractors have to admit, however, that what started as a social media call for justice when George Zimmerman was acquitted of shooting and killing the unarmed Black young man named Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida has become a global force.

What's not so clear is whether that's because of or despite the fact that BLM operates under a highly decentralized structure. It seems just about anyone can start up a Black Lives Matter outpost wherever they see fit.

Advertisement

"An organization has to have a mission," says Christopher Neck, a management professor at Arizona State University. "In terms of a social or political group, it's really difficult to control the mission and the message in a decentralized situation."

BLM's mission, according to its website, is to promote "the validity of Black life" and "(re)build the Black liberation movement." Much of that work to date has centered on calling attention to police shootings of unarmed Black men and to highlight racial inequities in the criminal justice system. But just how the movement should be carrying out that work sometimes depends on who you talk to. BLM's decentralized structure urges supporters to set up their own local chapters under the movement's flag. The group's grassroots founders Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi serve as figureheads and organizers but largely appear to let local chapters do their own thing.

That arrangement has caused confusion at times. Some Black Lives Matter members and their supporters were left scratching their heads, for example, when a Seattle chapter interrupted a Bernie Sanders rally to accuse the lefty presidential candidate and his campaign of racial bigotry. One member of a separate BLM faction in Seattle later issued a formal apology. Then BLM's founders piped up to say they'd made no such contrition.

Similar uncertainty unfolded in Atlanta, when a man claiming to be president of the local BLM chapter appeared at a press conference with the city's mayor to promote dialogue between the movement and the local government. Other activists claiming the Black Lives Matter flag said instead that the man was an aspiring actor with little attachment to the group, freelancing in front of cameras for his own personal gain.

Those types of mixed messages aren't exactly unexpected in a loose organizational structure, according to Ben Pauli, a social science professor at Kettering University in Flint, Michigan. But the decentralized approach also has its benefits. That includes giving the movement an organic, authentic feel and allowing members the sense that they are shaping its direction.

"When a movement like this starts up on a large scale, in a short time period and in many different places, it is often seen as capturing some kind of zeitgeist," Pauli says. "The idea assumes that it wouldn't be possible for the movement to arise in this way if many people weren't having similar experiences and feelings and needs. That gives it a sort of legitimacy."

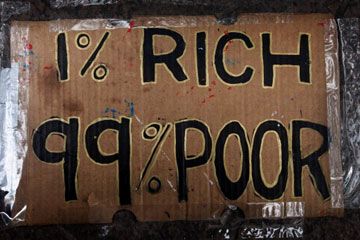

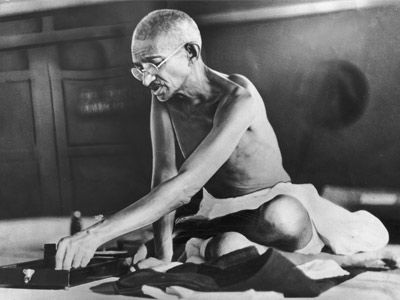

BLM's structure looks a lot like the Occupy Wall Street movement, which made a name for itself when protesters turned a park across the street from the financial center of the world into an open air campsite. But Pauli, who has been involved in social activism surrounding the Flint water crisis, says Black Lives Matter might be better served by looking to the Catholic Worker movement. That decentralized social justice initiative has launched a number of service-oriented communities around the globe. It has also lived on for decades following the death of leader Dorothy Day. The Worker's work continues, according to Pauli, because of the example that Day set for the movement at large.

"I'm convinced that a lot of it has to do with a certain kind of leadership and a certain kind of authority," Pauli says of Catholic Worker's staying power. "Dorothy Day was not somebody who was looking for followers. I like to call hers an exemplary authority: what she was trying to inspire was not followers, but for people to live out the kinds of principles that she embodied in her own personal behavior, knowing that they would do it in a variety of ways."

On the other hand, Arizona State's Neck says BLM activists could also look to the business community for what might be an unexpected model if they want to control their civil rights message. It starts with a red-headed, hamburger pushing clown.

"Instead of looking at a social activist organization, let's say you're a McDonald's franchisee," Neck says. "If you want to have the McDonald's name and you don't want to lose the money that you put in, you have to follow their rules."

Advertisement