At first glance, Afrofuturism seems like it was made for this moment. That seems fitting, considering Blackness is the commodity du jour (see: hip-hop, viral dances, popular slang). And science fiction, fantasy and magic dominate Hollywood storytelling (see: Marvel, "Star Wars," "Game of Thrones"). From a cynical perspective, it could seem like the math is simple: For maximum effect and financial gain, add the two.

Recently, we've seen Black stories aligned with speculative narratives in works like the 2018 movie "Black Panther," and the miniseries' "Lovecraft Country" and "The Falcon and the Winter Soldier." ("Speculative" means the book or movie has a setting other than the real world — for instance, it might take place in a future world or in a fantasy realm.) These tales address contemporary conversations around race, technology and progress while remaining rooted in speculative fiction traditions. But we can't imply that these kinds of stories are new and chalk their rise up to the opportunism and business savvy of media executives alone.

Advertisement

Afrofuturism isn't a product of the Hollywood machine or even the 21st century. It's actually a layered movement that has blossomed since critic and author Mark Dery coined the term in his 1994 essay "Black to the Future: Interviews With Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose."

In the essay, Dery questions why so few Black Americans wrote science fiction, especially since the genre seemed like the perfect vehicle for illustrating the complexity of Black American history and life.

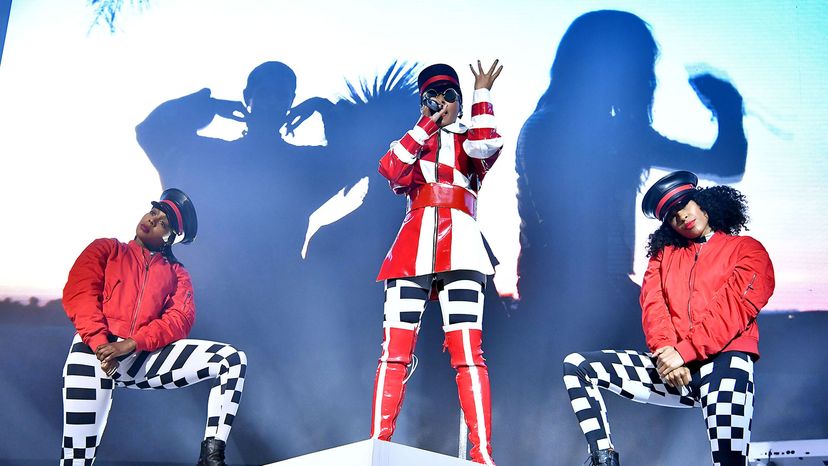

He went on to say that speculative fiction that treated African American themes in the context of the 20th century technoculture might be called Afrofuturism "for want of a better term." In Dery's shaping of it, Afrofuturism offers commentary on Black American concerns through a lens that incorporates science, technology and culture. You can see it in the music of Parliament-Funkadelic, the artwork of Jean-Michel Basquiat and the novels of Octavia Butler. Afrofuturism is not just about placing a Black person in a futuristic landscape. It takes into account the specific challenges that Black people face and allows them to imagine futures of their own making.

Advertisement