"OK" is probably the most spoken word in the world — besides English, people say "OK" in a dozen languages, including Spanish, Italian and Russian — and yet almost nobody can tell you what those two letters stand for or where the word came from.

Was it borrowed from the indigenous Choctaw word "okeh," meaning, roughly, "OK"? Did it originate with a Boston baker named Otto Kimmel who liked to frost his initials into his cookies? Does it have anything to do with the state of Oklahoma (OK) or the musical "Oklahoma!"?

Advertisement

Nope, nope and nope. In fact, there's no evidence that "okeh" was part of the Chocktaw language.

"OK is the greatest American word," says Anatoly Liberman, a linguist, translator and language professor at the University of Minnesota. "The history of OK is a history of incredible success, but nobody could have predicted that success."

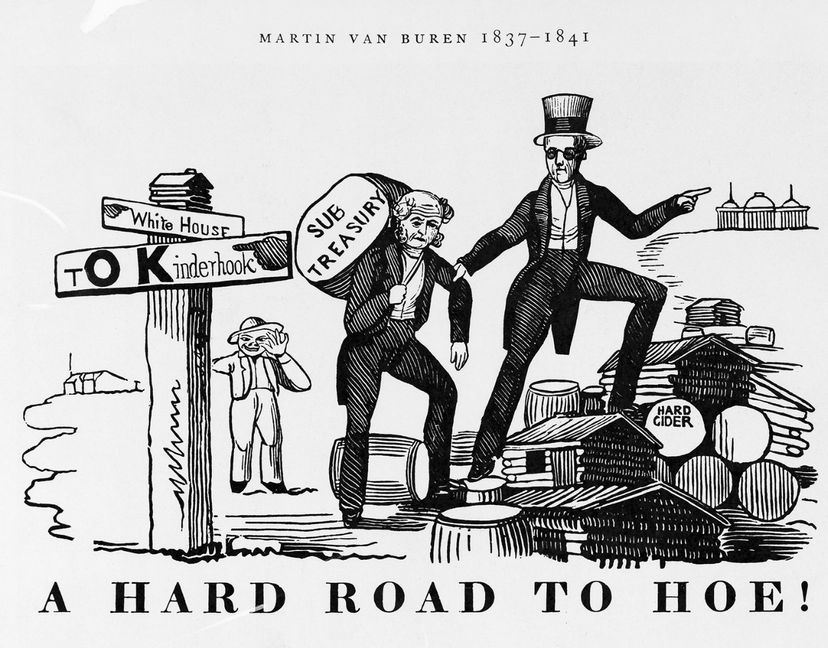

As you'll see, OK began as a piece of insider slang from the late 1830s and rode a (losing) presidential campaign to nationwide fame and eventually worldwide ubiquity.

Advertisement