If you're a fan of Clint Eastwood movies, the word punk is used to describe the variety of miscreants who make Dirty Harry's trigger finger itch. If you're a fan of Ashton Kutcher, the word might remind you of the practical jokes he and his friends played out on celebrities during the mid-2000s — on television no less.

Then there are gutter punks, those unkempt street people that often roam the urban landscape in packs, not to be confused with steampunks, the strange-looking hipsters who look like they traveled in time from the Victorian era after joining a pipefitters union.

Advertisement

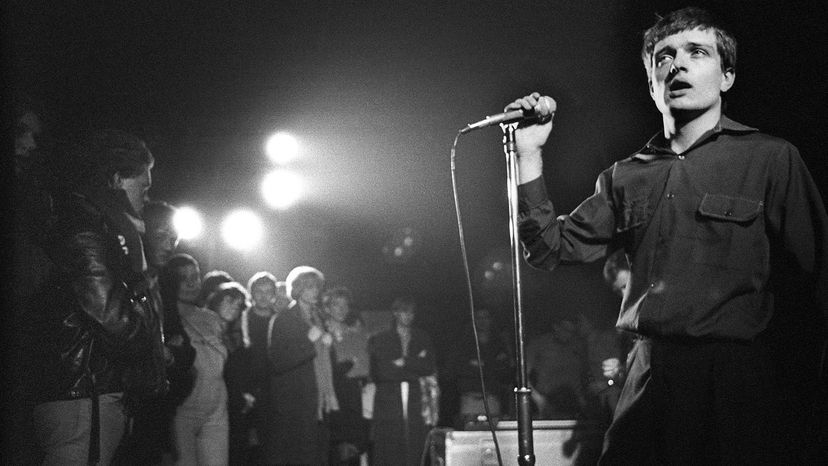

The point is, punk has many different meanings for many different people, but it is most commonly associated with a music and culture that started in the early 1970s and crested a decade later. Loud, fast and often angry songs featuring lots of down strokes on multiple electric guitars played by band members donning leather, ripped shirts, piercings and colorful mohawks are common descriptors of punk. The truth is, however, punk is way more than just about style and music. It began as a movement.

That movement brought together a wide range of people, sounds and styles. The common thread, according to punk historian and author of "We are the Clash: Reagan, Thatcher, and the Last Stand of a Band that Mattered" Mark Andersen, was a radical idealism. It was a sense of being socially outcast and the feeling that the rebel rock of previous generations had gone limp.

"The music and culture was generated by people on the margins and being a punk became a badge of honor," Andersen says. "It had some specific musical or fashion or hairstyle signifiers, but I think what is underneath all of that, and what is really the substance, is a challenging and creative spirit."

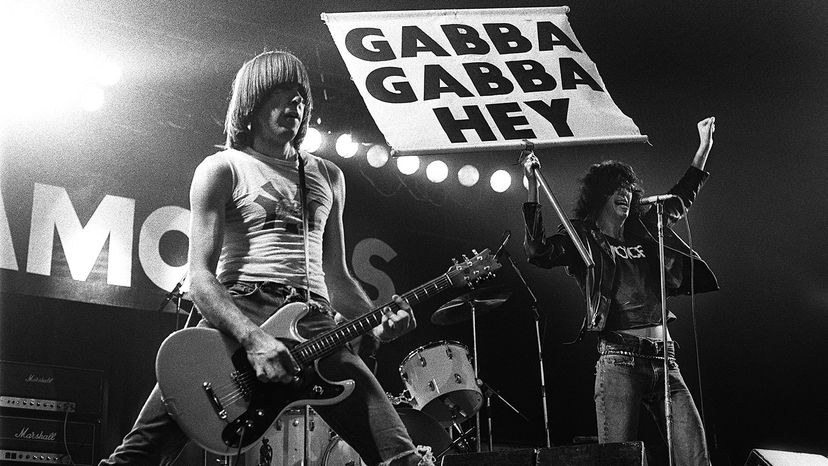

Johnny Ramone was a cofounder and lead guitarist for the New York City band the Ramones that helped put punk on the map. He told Rolling Stone in a 1976 interview that his band formed around a mutual feeling of exile, especially in their romantic pursuit of women.

"They always wanted to go with guys who had Corvettes, so we had nothing to do but climb on rooftops and sniff glue," he said.

Although punk's popularity has ebbed and flowed over the years, it's safe to say no one should be writing an obituary for it anytime soon. From Patti Smith, Iggy Pop and the New York Dolls to the Ramones, the Sex Pistols and The Clash, punk rockers have had a sweeping influence on music and culture. It can still be seen some 40 years after Sid Vicious died and more than a decade since the lights went off at the famed punk rock and new wave club CBGB in New York City.

The story of punk is a tale of youthful rebellion that ushered out the flower power and Nixon generation, replaced by something a little less hopeful and much darker around the edges. If hippies smoked weed, held hands and pranced around in circles chanting "give peace a chance," punks spiked heroin into their veins, slam danced on dirty club floors and yelled, "I wanna be your dog."

Advertisement