Collections are by definition kind of weird. Collectors devote days, weeks, months, even years to compiling excessive quantities of stamps they'll never mail, coins they'll never spend, hair they'll never — wait, what? Yes, you read that right: hair. Nineteenth-century lawyer and naturalist Peter A. Browne has the distinction of having cultivated the world's greatest hair collection. Sort of makes your prized record collection seem boring, doesn't it?

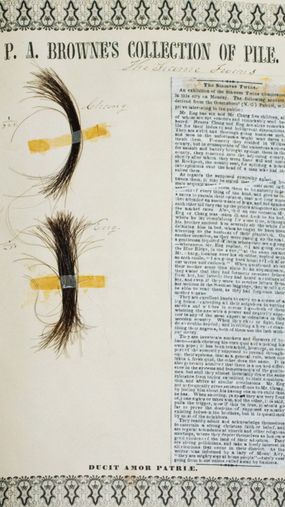

In the 1840s and '50s, Browne decided he would try to piece together a scientific portrait of humanity by obtaining as many hair specimens as possible. He wanted strands from famous figures, regular folks, living, dead — basically, if a person had hair, Browne wanted it. He collected samples from a fetus, a 100-year-old man, patients in the Western Virginia Lunatic Asylum, celebrities, conjoined twins, a corpse that had been buried for 32 years, and a convicted murderer (before and after his hanging, of course). Browne even had a few strands of George Washington's hair, courtesy of the late president's barber's son. He actually had samples from 13 of the first 14 U.S. presidents. So, all in all, a pretty terrifyingly thorough collection.

Advertisement

What exactly was the point of all this hair gathering, you might ask? According to the book "Specimens of Hair: The Curious Collection of Peter A. Browne" by Robert McCracken Peck, Browne was on a mission to explain the differences and similarities between humans. Years before Charles Darwin blew the world's collective mind with his theory of evolution, Browne obsessively sought to understand how and why there was so much variance in humans.

"His fellow members of the Academy of Natural Sciences were doing the same things with birds and insects and fish, and trying to figure out what were the distinctive characteristics that separated one from another, and combined one with another," Peck told the arts and culture website Hyperallergic. "With humans, that became a much more fraught political and social issue. Any attempt he made to separate people into separate species, as he called them at the time, was doomed to failure, and rightly so, because we recognize that all humans are from the same origin."

But Browne didn't know that. So, he collected. And perhaps the weirdest part about his weird collection is that for the era, it wasn't considered weird at all. "The collection may seem 'weird' by today's standards, but at the time it was made it was considered very important by scientists around the world," Peck said in an interview with The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University (ANSP), where is he is a senior fellow. "Browne referred to it as a national collection. It contained not just the hair of humans, but the wool of sheep and the fur and hair of many other mammals. It was a collection made for scientific purposes and for the love of country."

And if you don't believe that Browne's hair collecting compulsion wasn't all that odd for the era, consider this news story out of the U.K., where a woman stumbled upon a ring containing Charlotte Brontë's locks. While wading through her late father-in-law's attic, the unidentified woman from Erddig, Wales unlocked a curious metal box and found a single ring inside inscribed with Brontë's name and the date of her death. So the woman did what anyone in sudden unexpected possession of an old trinket might do: She went on "Antiques Roadshow." On the show, she told jewelry expert Geoffrey Munn she suspected she might have accidentally inherited some of Brontë's strands. Munn wasn't fazed. "It was a convention to make jewelry out of hair in the 19th century," he said. "There was a terror of not being able to remember the face and character of the person who had died."

Apparently, before selfies and Snapchats pretty much ruined our lives, people often wove bits of hair into just about everything from rings and bracelets to cufflinks and more. "The hair of family and friends was commonly exchanged and retained throughout the 19th century," Peck told the ANSP blog. "It was often framed, kept in albums, or featured in jewelry. Today many parents still retain the hair from their child's first haircut, but it is rarely put on public display as it was during the Victorian era." It's also probably not as valuable as Brontë's; Munn told the lady with the ring that while her newly discovered jewelry was probably only worth about $32, the famous author's strands bumped up the value to about $26,000.

But back to Browne. While he never realized his (flawed and problematic) dream of separating the human race into 'species,' he did make an enduring contribution to modern science. "What is so useful about this collection now is all of that DNA is preserved, and he had no idea he was doing that when he sent out his requests to people for hair," Peck said in Hyperallergic. "He actually asked them to send the roots of the hair, the follicles — many of them did just clip it — but with the follicles attached, that is a goldmine."

And Peck isn't just the expert responsible for immortalizing Browne's legacy in words — he's also the guy who helped save it from total destruction. "In the mid-1970s, before anyone recognized the importance and irreplaceable value of the DNA contained in Browne's collection, a staff member in a position to determine its fate decided that the wool, fur and human hair it contained was of no (current) scientific interest and was taking up too much space and he decided to discard it," Peck told the ANSP blog. "I was lucky to be in the right place at the right time to spot it and save it from oblivion. Who would have guessed it would one day become a collection of such interest and the subject of a book?!"

Advertisement