It is very likely that before the I Ching, sets of bones were cast in an attempt to know the future. These oracle bones, unearthed by archaeologists, were precursors to the divination system that is now used in the "I," either a set of 50 yarrow sticks or a set of three coins.

Essentially, the I Ching is a system that has always been used to predict the future. More importantly, though, is its use as a book of wisdom. Because the readings it gives are simple, yet elegant, profound, and intuitive, it is often consulted for its advice and insight into human nature. It is also read simply as an account of human affairs. In many circles, the book is no less influential today than it was hundreds of years ago.

Just like the Judeo-Christian Bible, there is no certainty as to who actually wrote much of the I Ching. Sometime close to the dawn of recorded history, the main text itself came into being. About 3,000 years ago, during the Zhou dynasty, the first records of its existence appear.

Even then, the philosophers of the time recognized the fundamental principles already touched upon -- that in the beginning exists Tai Chi, The Great Ultimate, and from it springs the yin and the yang. The yin is symbolized in The Book of Changes by a broken line ( - - ) and the yang, by a solid line ( - ). How better to indicate a yielding, nurturing force than with a broken line and an active, aggressive force with a solid line?

Yin, Yang, and the Forces of Change

As has been suggested, yin is regarded as the feminine principle -- nurturing, reflective, and yielding in character. Yang is considered the masculine force -- active, intellectual, and dominant. Although they are opposites, the two forces complement each other. In their permutations and interactions, they are the forces responsible for the constant change we see in the world.

In terms of making predictions about the future, we can use our knowledge of yang and yin to come to some conclusions. We know, for example, that everything in this world is subject to change. Day will give way to night in the same way that summer will yield to winter. At the same time, we can see patterns and cycles within this framework of change. These patterns, for example, often repeat themselves with mathematical precision. We have also determined that the patterns, such as the 24-hour cycle of a day or the 12-month cycle of a year, will exhibit extremes of both yang and yin at different times. Knowing this, we can easily make simple projections about the future.

Events such as the moment of sunrise or the exact time and date of a high tide can now be predicted with relative ease. It was not always so. The first mathematicians who learned through their science to predict such events as a solar eclipse were regarded as wizards, and it is surprising that more of them were not executed as a result. These types of predictions, though, dealt largely with what we in the West consider to be the inanimate world.

By investigating more closely still, we can see that living things, including ourselves, are also subject to these same processes. Since these processes do not change and are always governing how we behave, they are considered to be universal laws. Once this idea is accepted, it is not so difficult to see how a system of divination with specifically human applications might be constructed.

The System

First, this system needs to organize the general categories of human experience. Then it must devise a method of evaluating which of these events would be most likely to happen at a particular time for a particular person. To their eternal credit, the authors of the I Ching have constructed just such a system.

By using the solid line ( - ) to represent yang and the broken line ( - - ) to represent yin, the I Ching can symbolically express a relationship between the two forces. The only drawback is that by using just these two symbols, only four relationships can be expressed, the relation of yang to itself (two solid lines), the relation of yin to itself (two sets of broken lines) and their relation to each other (two more cases with either a yin line on the bottom or a yang line on the bottom). The genius of the I Ching is that to create more categories, it organizes the two forces of yin and yang into sets of three separate lines, called the trigram. Now there are eight possibilities. Finally, each separate trigram is coupled with another trigram. From these two groups of three lines, one larger group of six lines is created. This is referred to as a hexagram.

The Trigrams and the Eight Forces of Nature

When grouped into threes, yin and yang now have eight possible combinations. In their wisdom, the ancient sages used these categories to symbolize the eight primeval forces of nature. When grouped into sixes, yin and yang have 64 possible combinations. The sages used these to describe the life situations common to all humanity.

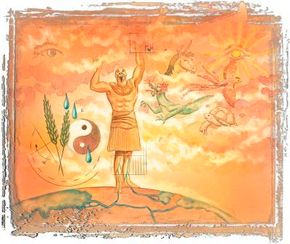

The origins of the eight trigrams are traditionally ascribed to the mythic ruler Fu-Hsi (Fuxi), who, as a divine being, had the body of a snake. According to the story, Fu-Hsi gave several incomparable gifts to humanity, including the skills of animal husbandry and fishing with nets. He also created musical instruments and a system of writing using knotted cords. Most importantly for the purpose at hand, he is credited with the development of the system of the eight trigrams.

His purpose in developing the trigrams was to organize all phenomena under heaven and earth and to place them within a simple and comprehensive framework. When arranged in a circular pattern around the Tai Chi symbol, the notation became known as Pa-Kua, the philosophical precursor of the I Ching. The symbols of Pa-Kua were likely devised as abstractions of the ancient myths. Given their original purpose, it is no wonder that the trigrams became the basis for the practice of divination.

One of the most appealing features about this system is its simplicity. According to its theory, all phenomena can be grouped according to one of eight principle trigrams, each of which becomes an icon in the process. The symbol identified as Heaven, for example, also encompasses such concepts as ruler, wealth, day, and father, to name just a few. Several thousand years ago, the world was very unlike our own. The world was then, it seems, much more straightforward and less complex. As the world changed, so did the system of Pa-Kua until it eventually developed into the comprehensive system of analysis known as the I Ching.

Learn more about I Ching hexagrams on the next page.

To learn more about tai chi, see: